Late Sunday afternoon. I woke up, choking! They are fogging again – the second consecutive weekend. Fogging is used extensively across Malaysia as a means of controlling mosquitoes, especially in the prevention of Dengue fever. However, its usefulness and effectiveness are coming into serious question. A recent exchange with researchers at Monash University revealed some interesting and also alarming concerns regarding its limited benefits, and its potential hazards.

Nature Regulates Itself

In the natural environment, there may be 20 species or more of mosquitoes that mainly feed on sugar/carbohydrate sources from plants. It is only the females who require a blood meal for egg production. Mosquito populations are themselves regulated by the presence of large numbers of natural predators such as bats, birds, dragonflies, wasps, spiders, and even insect-eating plants.

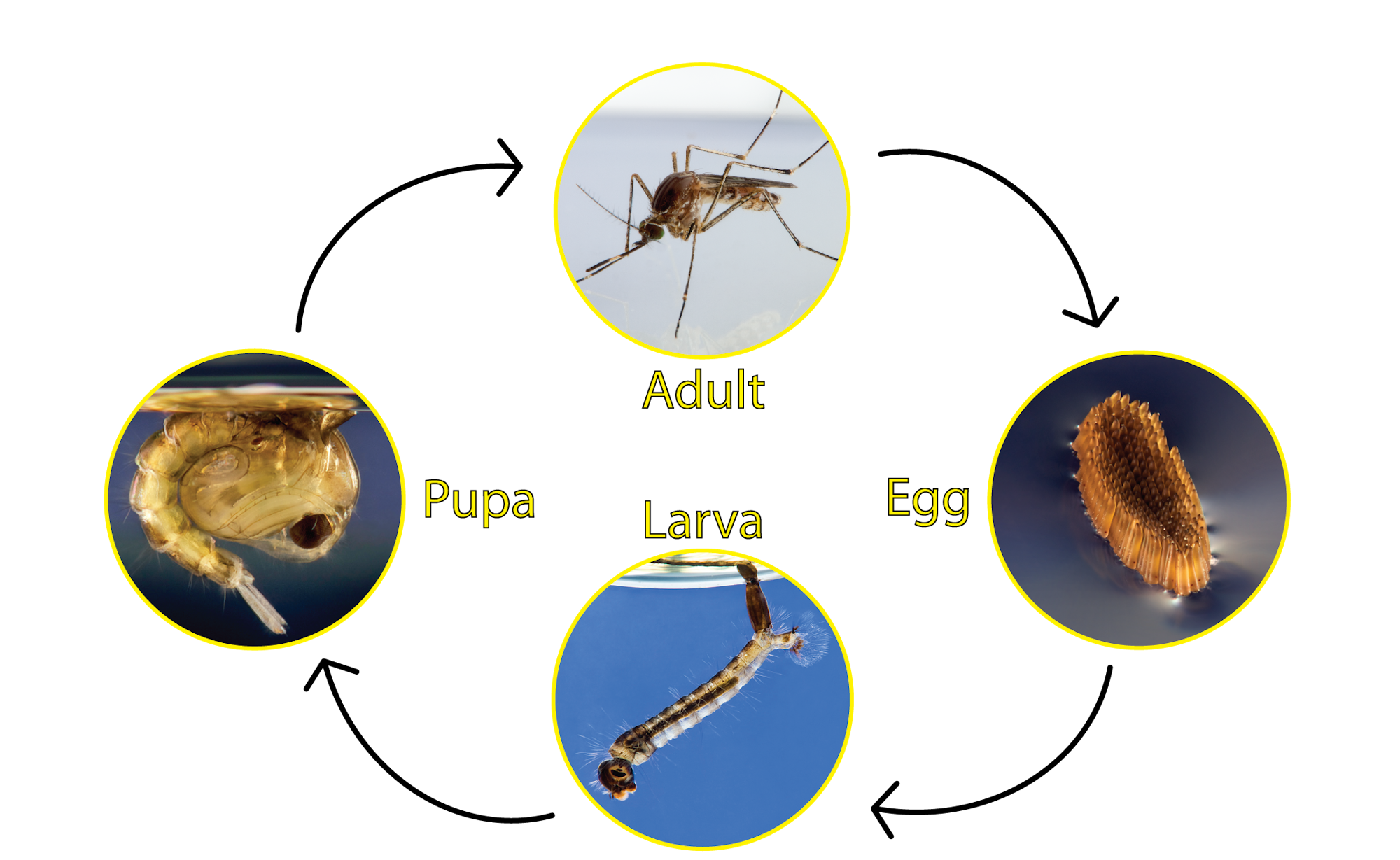

The larvae too, being water-borne, are predated upon by fish, dragonfly larvae and others. But, as the fog mist is airborne, that stage of the life cycle is otherwise protected from fogging.

Urban Environments

The situation in the urban environment appears to be different in many ways. Here, there is a limited number of mosquito species (principally two) that are both potential vectors of Dengue. However, there is much less vegetation and fewer natural water sources for egg laying and larvae development. Instead, the mosquitos resort to any source of residual water for that purpose, and it does not have to be clean.

Consequently, this includes all manner of man-made opportunities such as bottles, cans, buckets, old shoes, tyres, even coconut husks, anything that will retain even a few centimetres of water. Perhaps due to the often warmer and constant conditions of the city, the urban life cycle of the larval stage also appears to be accelerated compared with that in the wild.

Fogging – A Sledge-Hammer To Crack A Nut

Fogging is at best a sledge-hammer to crack a nut approach to tackling the problem of a disease like Dengue. The insecticides released (it has to be said, very wastefully) are not as selective as the manufacturers would claim and have harmful effects on nearly all other insects they come into contact with. They are also fatal against non-insect species, such as spiders, that are themselves natural predators of mosquitoes. Research in other areas has often shown that random, reckless and unregulated use of insecticides can have catastrophic effects on ecosystems by removing other key species that maintain a healthy balance (look at what happened when DDT was introduced). The drifting fogs deposit their deadly load on vegetation beyond the killing zone which then affects other species and their larvae, and these too become victims of fogging. This includes butterflies and moths, bees and wasps, stick insects and mantises, and thousands more.

Fogging Chemicals Do Not Discriminate

While this collateral damage can be significant, and potentially catastrophic in the long-term, there is ample and growing evidence that it is not effective in controlling mosquito populations. It has been shown in many studies that accumulation of insecticides in the bodies of predators higher up in the food chain can lead to reproductive disruption and the subsequent extinction of those local populations. At the same time, especially if the other species affected are key pollinators (such as bees and butterflies) of a particular tree, fruit or other food plant, then there can be a huge impact on the food chains for humans in the future.

What Is The Research Showing?

Apart from all the evidence supporting the earlier paragraphs, I understand that research has also shown that many people who have never been diagnosed with Dengue actually have antibodies in their blood. Interestingly, this indicates that they have been exposed to Dengue at some time previously, but that perhaps their symptoms were not significant.

{So, not everyone who contracts Dengue is aware of it or even suffers from the disease. Other studies (relating to bubonic plague and to AIDS for example) have shown that many of us carry a genetic defence against certain potential diseases. This would explain why not everyone is susceptible, and may also explain why not all of us are susceptible even to COVD-19.}

The whole issue of fogging is a scatter gun approach often used to address and allay the concerns of communities where cases have been diagnosed, using a method which was endorsed by WHO (World Health Organisation) many years ago. However, in a recent article from WHO, ‘fogging’ was not mentioned directly as a recommended deterrent, ‘except in a specific area where Dengue is shown to be present. The method is often customer-driven; residents complain to landlords or local authorities and the foggers are brought in.

Suppliers of these services and the chemical manufacturers enjoy benefits in terms of income, but with no responsibility for the actual efficacy nor overall long-term effects of their activities. Take the case of the fogging contractor in Colorado who was sent to prison under US Clear Air Act violation for his random dispersal of insecticide from the back of a truck.

And It Is Often The Poorest Who Are Most At Risk

Personal observation has revealed fogging on an unprecedented scale taking place in multi-level car parks, below condominiums for example, where there is no vegetation, nor much in the way of artificial reservoirs such as cans and bottles. The fog is soon dissipated by the breeze but residents are exposed to short-term choking fumes that would appear not to solve their problems in terms of the mosquitoes, and residents on higher floors (like myself) often experience an increased number of mosquitoes as they themselves seek to escape the choking fog below. Once the fog is indoors, it can take some time for it to dissipate.

However, other insect populations are themselves also decimated to the point where many children are not able to describe seeing a butterfly or a bee in or near their home which is already devoid of naturally occurring trees and shrubs. How sad is that?

Is Malaysia Typical In Its Approach To Dengue?

Sadly, like many other countries (and not just in Asia), Malaysia appears to be ‘over-focused’ on developing technical and chemical solutions rather than learning from nature and encouraging natural solutions. These might include improved planting and reforestation in urban areas, and perhaps a more common-sense approach such as improving community awareness, environmental hygiene, and better enforcement of health and safety regulations. Together, such measures would encourage the role and impact of natural predators, as well as reducing littering and dangerous disposal of ‘man-made’ waste, and generally improving the quality of our living spaces, including the air we breathe. In time, it may even be possible to develop a host-specific biological deterrent that may render the mosquitos infertile (this has been done before).

Future Challenges and Call to Action

The challenges to taking this road to reduce and eventually eradicate random fogging, while also tackling the incidence of Dengue, include:

- Raising Public Awareness of the risks of poor domestic and commercial hygiene, and to seek opportunities to work with nature to achieve a safer environment (removing nature from the cities is not the answer)

- Challenging the industrial lobby that promotes the production and frequent application of such insecticides to better regulate supply and distribution

- Getting Government support to provide directives to regulate the use of such insecticides, their concentrations and frequency, and to enforce those regulations, and to have a commitment to more research on the potential adverse effects on the human population.

All of the above will require strategies to address them, but simply ensuring better housekeeping and awareness in communities would have a significant impact on reducing the incidence of mosquito-borne disease and keep us safer. Let’s start there! – New Malaysia Herald

About the Writer: Retired from a career in hospital management, Dominic has been resident in Malaysia now for three years. From an early age, he has had a passion for nature. He recently trained as a Climate Reality Leader (part of US VP Al Gore’s campaign) raising awareness of the seriousness of the Climate Emergency and what we have to do to address it. He is committed to bringing a common sense perspective to issues that he believes need to be shared and debated.

Facebook Comments